JOHN GREENWOOD

‘You have awakened not out of sleep, but into a prior dream, and that dream lies within another, and so on, to infinity …

‘The Writing of the Gods’ Jorge Luis Borges

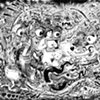

Looking at John Greenwood’s paintings feels rather like staring into a cell, a place of confinement, open on one side only—the viewer’s. These are paintings of species and spaces that beggar belief. ‘I like it sometimes that I create a believable illusion of something that has never existed.’

Greenwood is inspired, in part, by Cotán’s bodegóns, 17th century Spanish still life paintings with parabolic hangings of cabbages, melons, weird carrots and threaded sparrows. Cotán, for Greenwood, is king of a heap composed of many other still life painters: de Heem, Ruysch, Coorte, Kalf and Chardin to name but a few. Cotan is, he says, ‘the stubborn avocado stone that refuses to be integrated into this mush.’ Greenwood is an unapologetic raider of other people’s paintings. There is a combative streak to him: he wants to be ‘king of the compost heap’. To his mind, art of the past must be fermented and feasted upon to bring nourishment to his own. And what a mush of things and qualities lie buried there: things that hang, overflow, ooze, bulge, and glisten; lunar cheeses, velvet peaches and barnacled bread. None, however, appear directly in Greenwood’s paintings. Instead they await transformation in the heat of the ferment. Only then do glass vases in the floral still lives of de Heem and Ruysch emerge as ‘objects that have observable internal spaces, viewable through glass, crystal, or inflated transparent membranes’. Observable maybe, but also, perversely inaccessible.

Through the use of one point perspective and impeccable painting technique Greenwood imprisons his symmetrical creations in confined and claustrophobic spaces. In doing so he brings a mixture of humour and pathos to their pointless wrigglings and fumblings, squashings and balloonings. ‘Will they fall flat, dilate, deflate, or dissolve?’ Amusing speculation for the viewer perhaps, but underlying their absurdity there is also a sense of outrage rumbling away. Of a recent painting, El Dorado, Greenwood writes: ‘As I worked on this I felt its heart lay in this post-Thatcherite/Reaganite world where we're meant to function as desire machines, mindlessly consuming the world.’ The symbolic still lives painted for the newly prosperous Dutch Republic were intended to warn of the moral perils of this compulsion to consume and flaunt. In Greenwood’s paintings, dysfunctional desire and material excess are similarly exposed; just this time it is as disorderly, pretty, playful, repulsive things that over-extend themselves with limpid gestures within clinical confines.

There is no window onto the world in these interiors. There is no light source from without or within other than that provided by the artist himself. No other world is implied or invited in; it is a world of a singular imagination. As such, Greenwood’s highly personal, obsessive and absurdist practice recalls the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch or Yves Tanguy, the animated films of Jan Švankmajer, or the sculpture of Cathy de Monchaux.

‘The carving out of space is essential to the works, whether as spaces to allow the depicted objects to live, or as implied spaces around, or within which, to create their character’ states Greenwood. Georges Perec, melancholic author of Species of Spaces and other Places asks: ‘What does it mean to live in a room? Is to live in a place to take possession of it? Greenwood certainly takes possession of his ‘rooms’. Having imposed severe constraints on their depth of field he makes their scale and situation ambiguous and open to interpretation: ‘the allusion to realistic proportions, where the object is life size; or possibly inflated from some microscopic investigation; or my favourite, an implied vast disjuncture of scale to the cosmic, where the small, decorative baubles refer to much bigger entities, rendering the small space a model in a child's bedroom.’

Greenwood’s process is ‘pre-verbal, or sub-verbal’ he suggests, but behind such a modest claim there would seem to lie an inconsolable imagination being put into play.

Frances Woodley September 2016

‘You have awakened not out of sleep, but into a prior dream, and that dream lies within another, and so on, to infinity …

‘The Writing of the Gods’ Jorge Luis Borges

Looking at John Greenwood’s paintings feels rather like staring into a cell, a place of confinement, open on one side only—the viewer’s. These are paintings of species and spaces that beggar belief. ‘I like it sometimes that I create a believable illusion of something that has never existed.’

Greenwood is inspired, in part, by Cotán’s bodegóns, 17th century Spanish still life paintings with parabolic hangings of cabbages, melons, weird carrots and threaded sparrows. Cotán, for Greenwood, is king of a heap composed of many other still life painters: de Heem, Ruysch, Coorte, Kalf and Chardin to name but a few. Cotan is, he says, ‘the stubborn avocado stone that refuses to be integrated into this mush.’ Greenwood is an unapologetic raider of other people’s paintings. There is a combative streak to him: he wants to be ‘king of the compost heap’. To his mind, art of the past must be fermented and feasted upon to bring nourishment to his own. And what a mush of things and qualities lie buried there: things that hang, overflow, ooze, bulge, and glisten; lunar cheeses, velvet peaches and barnacled bread. None, however, appear directly in Greenwood’s paintings. Instead they await transformation in the heat of the ferment. Only then do glass vases in the floral still lives of de Heem and Ruysch emerge as ‘objects that have observable internal spaces, viewable through glass, crystal, or inflated transparent membranes’. Observable maybe, but also, perversely inaccessible.

Through the use of one point perspective and impeccable painting technique Greenwood imprisons his symmetrical creations in confined and claustrophobic spaces. In doing so he brings a mixture of humour and pathos to their pointless wrigglings and fumblings, squashings and balloonings. ‘Will they fall flat, dilate, deflate, or dissolve?’ Amusing speculation for the viewer perhaps, but underlying their absurdity there is also a sense of outrage rumbling away. Of a recent painting, El Dorado, Greenwood writes: ‘As I worked on this I felt its heart lay in this post-Thatcherite/Reaganite world where we're meant to function as desire machines, mindlessly consuming the world.’ The symbolic still lives painted for the newly prosperous Dutch Republic were intended to warn of the moral perils of this compulsion to consume and flaunt. In Greenwood’s paintings, dysfunctional desire and material excess are similarly exposed; just this time it is as disorderly, pretty, playful, repulsive things that over-extend themselves with limpid gestures within clinical confines.

There is no window onto the world in these interiors. There is no light source from without or within other than that provided by the artist himself. No other world is implied or invited in; it is a world of a singular imagination. As such, Greenwood’s highly personal, obsessive and absurdist practice recalls the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch or Yves Tanguy, the animated films of Jan Švankmajer, or the sculpture of Cathy de Monchaux.

‘The carving out of space is essential to the works, whether as spaces to allow the depicted objects to live, or as implied spaces around, or within which, to create their character’ states Greenwood. Georges Perec, melancholic author of Species of Spaces and other Places asks: ‘What does it mean to live in a room? Is to live in a place to take possession of it? Greenwood certainly takes possession of his ‘rooms’. Having imposed severe constraints on their depth of field he makes their scale and situation ambiguous and open to interpretation: ‘the allusion to realistic proportions, where the object is life size; or possibly inflated from some microscopic investigation; or my favourite, an implied vast disjuncture of scale to the cosmic, where the small, decorative baubles refer to much bigger entities, rendering the small space a model in a child's bedroom.’

Greenwood’s process is ‘pre-verbal, or sub-verbal’ he suggests, but behind such a modest claim there would seem to lie an inconsolable imagination being put into play.

Frances Woodley September 2016